Software engineering, and by extension data engineering, has many well-known acronyms. DRY, YAGNI, KISS, RTFM, SRP - they certainly ring a bell. But what about DAMP? Despite being less popular, this acronym also has a beneficial impact on your data engineering projects.

Data Engineering Design Patterns

Looking for a book that defines and solves most common data engineering problems? I wrote

one on that topic! You can read it online

on the O'Reilly platform,

or get a print copy on Amazon.

I also help solve your data engineering problems 👉 contact@waitingforcode.com 📩

DAMP stands for Descriptive And Meaningful Phrases. It's an idea that emerged in the mid-2010s to somewhat counterbalance DRY. Why counterbalance? Let's look at an example of a function that, depending on a flag, performs a specific action:

def decorate_order(order: Order, is_raw: bool, is_enriched: bool) -> DecoratedOrder:

if is_raw:

order = order.enrich_order()

elif is_enriched:

order.raw_data = fetch_raw_data_for_order(order)

decoration_metadata = fetch_decoration_metadata(order)

return order.to_decorated(decoration_metadata)

The function looks okay, but I bet there is something that will be problematic for your future self or your new colleagues: readability. The is_raw and is_enriched flags are pretty innocent at the moment. You have just written this function and know exactly what each flag does. But this clarity is not guaranteed in the future. It's only a tiny part of your codebase, and there are probably many other tiny things to remember. Believe it or not, you will have many other things to remember from both your private and professional life between now and the day you need to change this function. So now the question arises: what is the best way to remember? Simply, by not having to! Let's see how to achieve this by giving it a more meaningful name - a more descriptive and meaningful phrase:

def _decorate_order(order: Order) -> DecoratedOrder:

decoration_metadata = fetch_decoration_metadata(order)

return order.to_decorated(decoration_metadata)

def decorate_raw_order_after_enrichment(order: Order) -> DecoratedOrder:

order = order.enrich_order()

return _decorate_order(order)

def decorate_enriched_order_after_raw_data_fetch(order: Order) -> DecoratedOrder:

order.raw_data = fetch_raw_data_for_order(order)

return _decorate_order(order)

I bet (and I'm not a gambler, yet I'll bet again) the code above is much more readable than the original one. Depending on the type of your Order, you call either the decorator for the raw format or the decorator for the enriched format. No flags, no hidden magic - just clear names!

In a nutshell, that's the hidden power of the DAMP - more meaningful and easy to understand code, even though it may require some repetitions like in our case with a duplicated call to the _decorate_order function.

The _decorate_order repetition is not the repetition in the sense of the business logic repetition. The repetition consists of having two places performing the order decoration while in the first snippet you saw there was only one snippet for that.

How to?

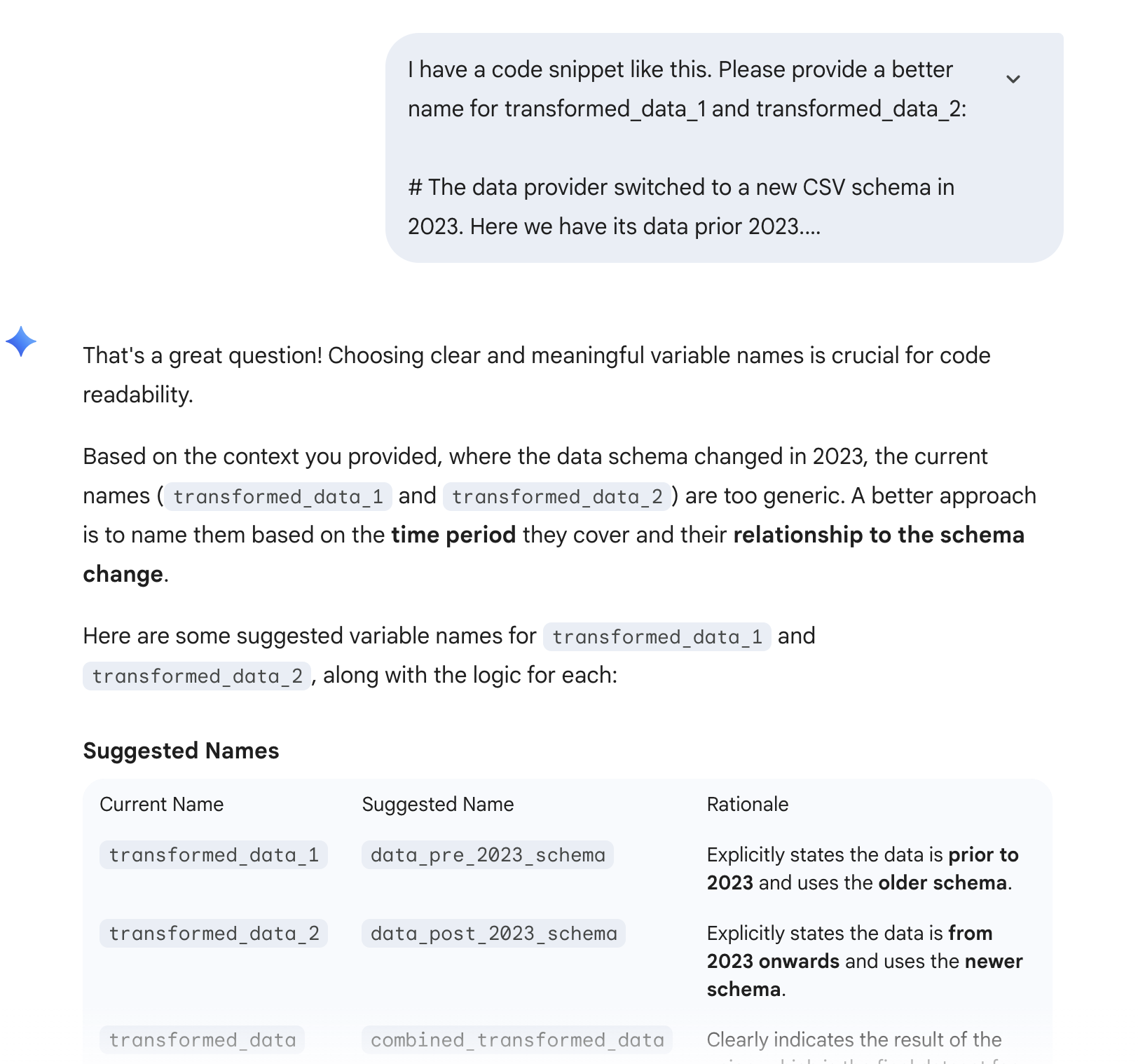

I hope after this quick example you better understand how well-chosen names can help you write more easily understandable code. But the challenge is how to choose these names. The easiest way nowadays is to ask your coding assistant by clearly describing what a function or variable does or is. The assistant will likely propose a few great names.

If you prefer an alternative, the best hack I've found is to add a comment one to three sentences long before the variable or function call. In the comment, try to articulate what the snippet is doing. Most of the time your comment will contain one or two keywords that you can use to choose a better name. See the demonstration below:

# The data provider switched to a new CSV schema in 2023. Here we have its data prior to 2023. transformed_data_1 = transform_data(path=file_path, years=[2020, 2021, 2022] transformed_data_2 = transform_data(path=file_path, years=[2023, 2024, 2025] # ...20 lines below # Combine pre 2023 and post 2023 data together for further common processing transformed_data = transformed_data_1.unionByName(transformed_data_2)

The variable names are poorly chosen, aren't they? What if we leveraged the inline comment to create a more meaningful code:

# The data provider switched to a new CSV schema in 2023. Here we have its data prior to 2023. transformed_data_prior_2023 = transform_data_prior_2023(path=file_path) transformed_data_after_2023 = transform_data_after_2023(path=file_path) # ...20 lines below transformed_data = transformed_data_prior_2023.unionByName(transformed_data_after_2023)

This refactoring brings clearer names and also reduces a mental effort to understand the code. The union is made 20 lines after the variables declaration and with the new names you don't need to jump to their definition to see what they contain.

Besides helping choosing the names, commenting also helps explain the snippet to other-you (aka Rubber duck debugging) which in its turn can spot some inconsistencies or trigger simplification in case the explanation is too complicated.

💡 Useful comments explaining the WHY

I didn't remove the comment explaining the schema switch on purpose. It's still a valuable resource in the code that can help immediately understand why there are two separate transformation calls instead of a single one.

Unit tests

Besides the core code logic, the place where you will appreciate the DAMP principle the most are unit tests. Let's take a look at the code below that tests orders DataFrame:

def create_test_dataset(spark_session: SparkSession) -> DataFrame:

return spark_session.createDataFrame([

Row(order_id=1, shipping_area='EU', completed=False),

Row(order_id=2, shipping_area='EU', completed=True),

Row(order_id=3, shipping_area='US', completed=True)

])

def filter_method_should_keep_only_completed_orders(generate_spark_session):

spark_session: SparkSession = generate_spark_session

test_data = create_test_dataset(spark_session)

completed_orders = filter_uncompleted_orders(test_data)

assertDataFrameEqual(completed_orders, spark_session.createDataFrame([

Row(order_id=2, shipping_area='EU', completed=True),

Row(order_id=3, shipping_area='US', completed=True)

]))

def aggregate_method_should_correctly_count_orders_in_areas(generate_spark_session):

spark_session: SparkSession = generate_spark_session

test_data = create_test_dataset(spark_session)

aggregated_orders = aggregate_orders_by_area(test_data)

assertDataFrameEqual(aggregated_orders, spark_session.createDataFrame([

Row(shipping_area='EU', count=2),

Row(shipping_area='US', count=1)

The code respects the DRY (Don't Repeat Yourself) principle because the orders are created in a single place. But there is a problem. If you are reading the test and want to know which dataset composition led to the expected results, you need to scroll up and then scroll back down, hoping you correctly remembered the definition. This is typically illustrated by asking yourself this question: Do my aggregated orders contain only completed orders?

Now that you've seen the DRY, but less readable, version, let's look at the alternative that doesn't respect the DRY principle but favors DAMP instead:

def filter_method_should_keep_only_completed_orders(generate_spark_session):

spark_session: SparkSession = generate_spark_session

test_data = spark_session.createDataFrame([

Row(order_id=1, shipping_area='EU', completed=False),

Row(order_id=2, shipping_area='EU', completed=True),

Row(order_id=3, shipping_area='US', completed=True)

])

completed_orders = filter_uncompleted_orders(test_data)

assertDataFrameEqual(completed_orders, spark_session.createDataFrame([

Row(order_id=2, shipping_area='EU', completed=True),

Row(order_id=3, shipping_area='US', completed=True)

]))

def aggregate_method_should_correctly_count_orders_in_areas(generate_spark_session):

spark_session: SparkSession = generate_spark_session

test_data = spark_session.createDataFrame([

Row(order_id=1, shipping_area='EU', completed=False),

Row(order_id=2, shipping_area='EU', completed=True),

Row(order_id=3, shipping_area='US', completed=True)

])

aggregated_orders = aggregate_orders_by_area(test_data)

assertDataFrameEqual(aggregated_orders, spark_session.createDataFrame([

Row(shipping_area='EU', count=2),

Row(shipping_area='US', count=1)

Clearly, you duplicate the dataset definition, but on the other hand, it gives you direct access to the unit test context. No need to scroll and leave your tested unit scope to get the definition. Everything is right there.

Does it mean you should avoid DRY in your tests logic? Not at all. Instead, you should adapt it for each use case. For example, a good reason for favoring DRY, hence coupling between tests that is a bad practice in general, over DAMP in unit tests is dataset freeze. In that scenario you need to use the same dataset for many test cases. Repeating the dataset, therefore adopting the DAMP-first approach, might lead to differences in the future where one test might add an additional row. Having the dataset in a central place, so adopting the DRY-first approach, doesn't bring this desynchronization risk.

Naming things is known to be one of the hardest problems in computer science (Phil Karlton). But having this science mastered at the satisfying level helps writing more maintainable code.

Consulting

With nearly 17 years of experience, including 9 as data engineer, I offer expert consulting to design and optimize scalable data solutions.

As an O’Reilly author, Data+AI Summit speaker, and blogger, I bring cutting-edge insights to modernize infrastructure, build robust pipelines, and

drive data-driven decision-making. Let's transform your data challenges into opportunities—reach out to elevate your data engineering game today!

👉 contact@waitingforcode.com

🔗 past projects